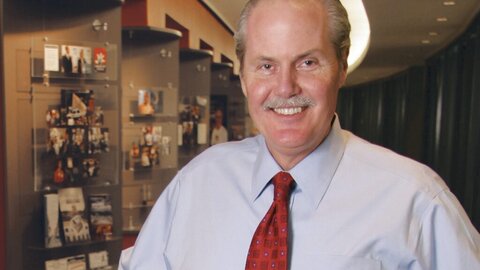

Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota is the poorest area in the nation, says Mary Jo Fairhead, a former public school teacher who grew up on the reservation. “I love it, but there are a lot of life issues,” she explains. “A lot of poverty, a lot of addiction issues. Our kids struggle with suicide and high dropout rates. Just a lot of hard things. And that’s really why I became a teacher—because I wanted to help kids.”

But when she got to the classroom, she didn’t feel like she was really helping. “Class sizes were huge, and I couldn’t get real meaningful lessons planned because I was just putting out fires all the time,” she recalls. “I got really frustrated with how the system was set up and the kids I was seeing falling through the cracks.” Her frustrations—with the discipline techniques, the structure of the day, the curriculum, and all the testing—pushed her to quit teaching.

After being home with her kids for a few years, she took a position as principal of a small preK‑8 public school. Mary Jo says she was excited about the job because, as principal, she figured she’d be able to do things the way she thought they should be done. “I really did enjoy that job. It was so hard emotionally, but I felt like we were doing some really good things. The kids were really making progress, and the teachers felt comfortable with me,” she says.

The main downside was the amount of testing they had to do—because their test scores were low, the kids had to do even more testing. “We were testing like five to six weeks out of the year, and that wasn’t even including the progress monitoring,” she says. “We had benchmark, we had the state testing, and then we had the progress monitoring. So it was just all this time around testing.” Meanwhile, she was mainly concerned with just keeping the kids alive.

Then COVID-19 hit, and they had strict lockdowns and didn’t see the kids for 13 months. When they finally went back, she was glad to see the kids, but she didn’t see herself there anymore. She told her husband she had to begin homeschooling or open her own school, and he said, “I guess we’re starting a school.” She quit her job without much of a plan and created Onward Learning.

Mary Jo started with six school-aged children and six in a childcare situation. She had 27 students by the end of the second year and started this year with 37 students and a long waitlist. “We just don’t have the capacity for more kids,” she says. “We’re just growing really fast.” Right now she has preschool and kindergarten in the upper level of her house, grades 1–4 in the lower level, and grades 5–8 in a space she rents. They’re in the process of building a new facility that she hopes will be able to serve 60 kids for next school year.

The kids spend a lot of time outdoors; Mary Jo has 3½ acres with lots of trees, a playground, and a nearby golf course. “We’re outside at least two hours a day, sometimes more. If it’s nice out, we bring our books outside and do all of our learning outside,” she says. “We also have a garage that we’ve turned into kind of an art studio. So we have a kiln in there, and we do all our painting and ceramics and things like that in there.”

They start each day outside no matter what the weather is. Then they come inside and have breakfast together—a local mom makes home-cooked breakfast, lunch, and snack each day. They work in small groups through the morning to cover math, English, reading, and science. All of the learning is personalized, so Mary Jo evaluates students when they come so she can start them where they are rather than where they “should” be.

After the core subjects, the kids have a break and then do music, art, or baking before lunch. After lunch is independent reading time, which Mary Jo says the kids love. She also reads aloud to them in the afternoons. Then they have what she calls curiosity classes. “Those are anything from painting to ceramics to woodworking, nature walks,” she explains. “Pretty much anything that they’re interested in.”

Mary Jo is finally able to teach the way she thinks it should be done. “I grew up going to a really small school, they call them country schools here, with multi-age learning—very similar to the microschools. And that’s what I knew and that’s what I loved,” she says. But that’s not what was happening when she was in public schools.

For other teachers who are feeling the same way and want to create their own microschool or other learning environment, Mary Jo offers encouragement. “Reach out to find other people who have done it and just ask questions and lean on them a little bit,” she says. “I think the biggest thing is just to not question yourself. You can do it. It seems daunting, but it’s really not.”